Philadelphia’s overdose deaths dip overall in 2018 but are ‘still at crisis levels’

In the worst urban drug crisis in America, an 8 percent dip is considered progress. But underlying trends continue to be troubling.

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-pmn.s3.amazonaws.com/public/3I2Y4UHNOVGILCBCFY6GUOGHQI.jpg)

Overdose deaths dropped slightly in Philadelphia in 2018 — with 1,116 people dying of accidental overdoses compared with 1,217 people the previous year, according to figures released by the city’s Department of Public Health on Tuesday.

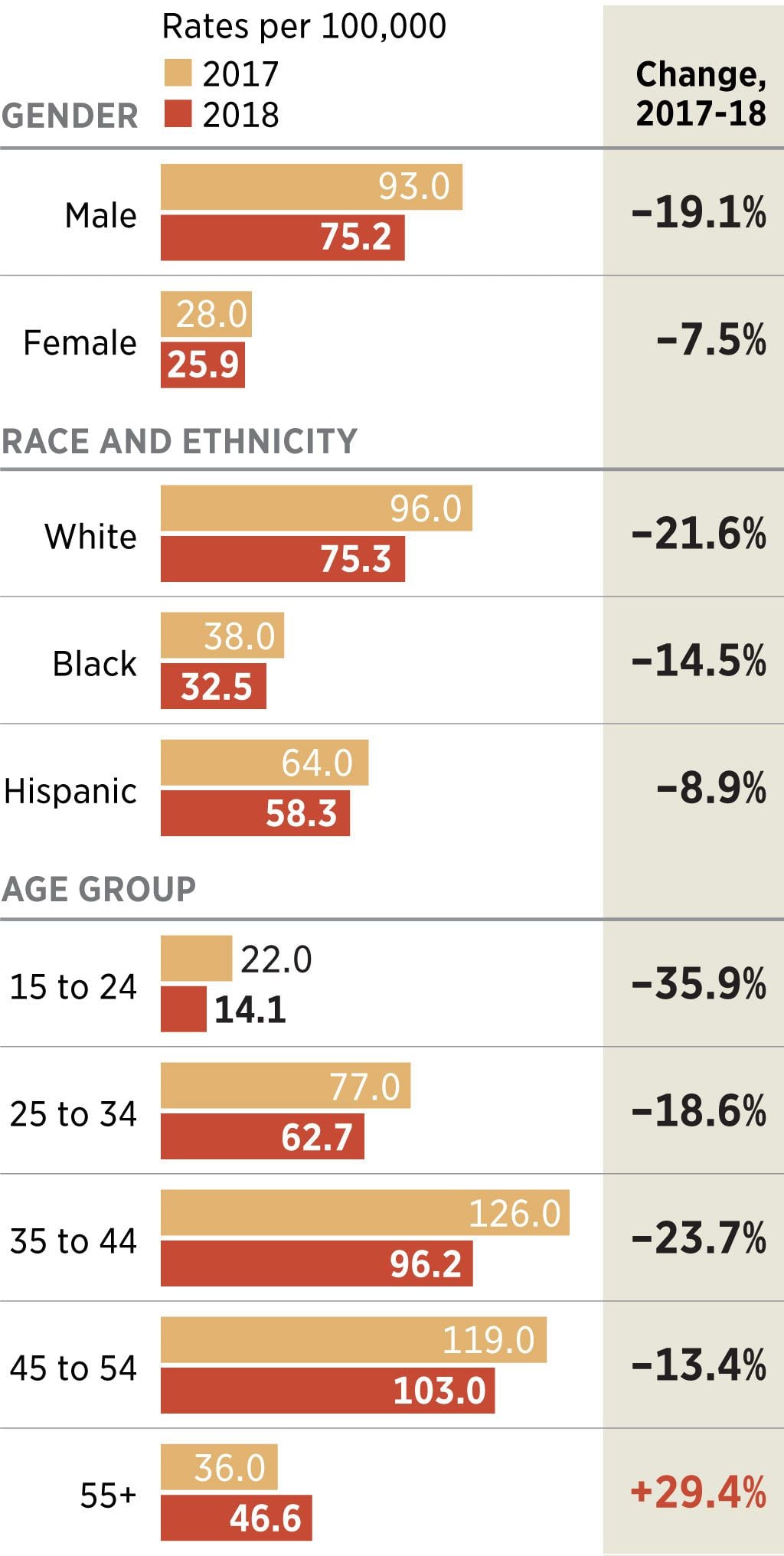

Still, the city’s opioid crisis remains among the worst in the nation, with an overdose rate more than triple the homicide rate. Deaths declined in most demographic groups, but the rate escalated sharply among victims ages 55 and up.

Death rates continue to be highest among white residents, for whom the fatal overdose rate was around 75 per 100,000 residents; followed by 58 for Hispanics and 32 for black residents.

Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley noted that the death rate still far exceeds what it was just a few years ago. "It’s still at crisis levels -- 1,116 deaths is an enormous number compared to where we were five, 10, 20 years ago. These are lives we can save.

“The real news here,” he said, “is not the size of the drop, but the fact that it dropped at all after unrelenting and huge increases.”

Much credit, officials say, goes to the fact that so much naloxone — the reversal drug also known by its brand name, Narcan — has been distributed that people often are saved from a deadly overdose by friends, family, police, even strangers.

It’s a common sight on the streets of Kensington, the Philadelphia neighborhood that has seen the largest number of deaths, though overdoses occur everywhere in the city.

Jesse Gibase, 23, has lived on the streets of Kensington for about a year since leaving his hometown of Chester. Camped outside of St. Francis Inn, the longtime soup kitchen on Kensington Avenue, on Tuesday, he says he’s seen more people on the streets getting “brought back” from overdoses because it seems like everyone has Narcan. If you don’t have any, he said, “all you have to do is scream ‘Narcan’ " and a vial will appear.

Though he came to Kensington originally to buy heroin, he’s now also using the potent synthetic cannabinoid K2 -- cut with fentanyl and other substances he cannot even name. It’s a mix that is getting more and more popular, he said.

The opioid epidemic largely has been painted as affecting mostly whites, who continue to make up the largest share of fatal overdoses. But Andre Burton, 30, a black man who has been using since he was 21 after getting prescribed Percocets for a football injury, sees all races affected. Interviewed in Kensington on Tuesday, he said he probably uses Narcan on five people a week.

“Chinese people shoot heroin,” he said, “Indian people shoot heroin. It doesn’t discriminate.”

Ashley Melendez, a 34-year-old mother of four, most recently relapsed after five months in recovery from a heroin addiction and returned to the streets a few weeks ago. A native of Kensington who’s Irish and Puerto Rican, she says the main differences she has seen are the prevalence of K2 and how easy it is to get free samples of drugs. People come out to Somerset and Kensington Avenues and call out, “Samples!” as they direct folks to certain corners. One free sample could last for the day, Melendez said, or else it’s possible to get multiple free samples from different dealers.

It’s not clear what is driving higher rates of overdose death in older adults. Farley said it’s possible that some in that group may have been using opioids “maybe since the heroin problem from the 1960s and 1970s." But now, they are encountering heroin mixed with the deadly synthetic opioid fentanyl.

Even with the spike, the death rate for those 55 and over remains less than half that of people between 45 and 54, which Farley termed “the most dangerous age” for an overdose. The impact on older adults, he said, is a sign of how the crisis began for many with a physician’s prescription.

“People who had painful conditions like arthritis went to their doctor and got opioids -- they initiated this drug use much older in life." Still, the fact that deaths solely from pain pills have dropped by more than half since 2012 is an encouraging sign that efforts to curb prescription patterns are working.

Philadelphia Overdose Demographics

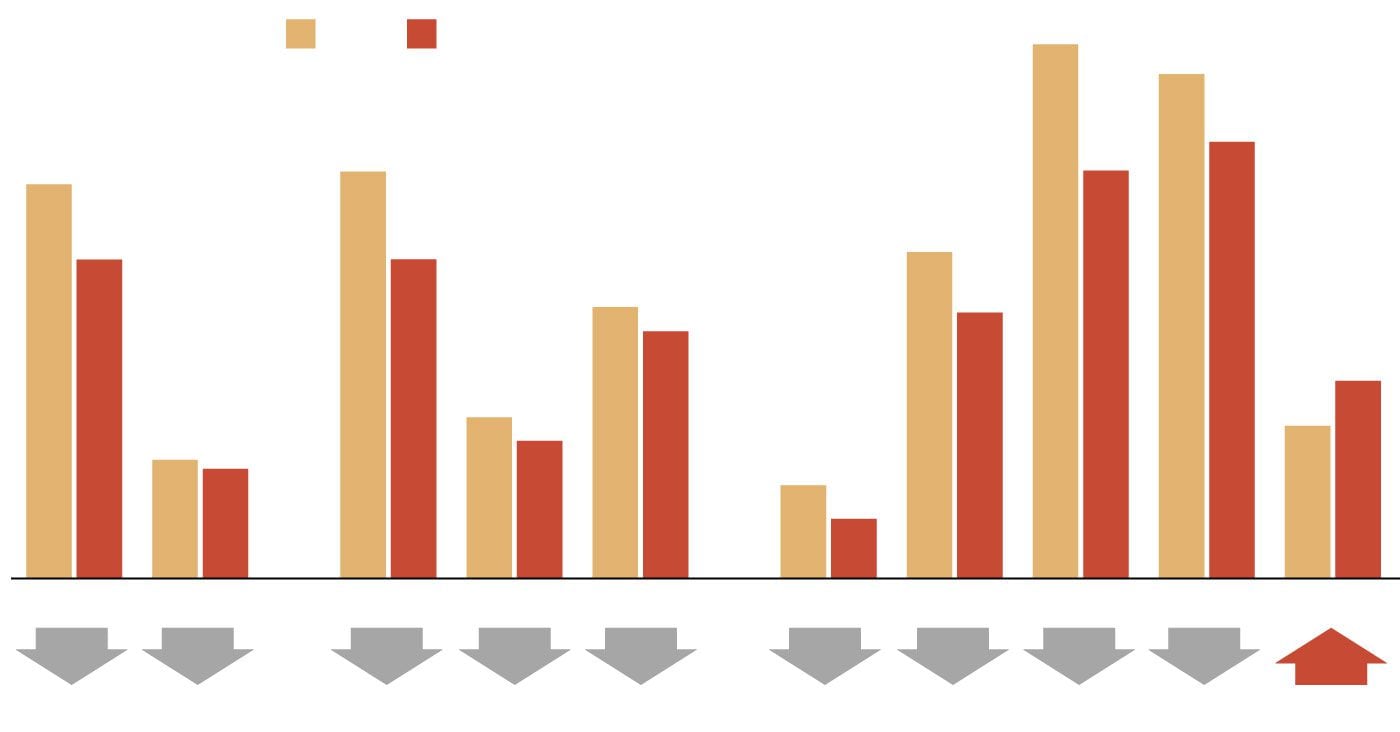

The rate of overdoses per 100,000 residents dropped from 2017 to 2018 across all genders, races and ethnicities, and ages, except for the 55-and-older age group.

126.0

2017

2018

Rates per 100,000:

119.0

103.0

96.0

96.2

93.0

77.0

75.2

75.3

64.0

62.7

58.3

46.6

38.0

36.0

32.5

28.0

25.9

22.0

14.1

Male

Female

White

Black

Hispanic

15-24

25-34

35-44

45-54

55+

19%

8%

22%

14%

9%

36%

19%

24%

13%

29%

Gender

Race and ethnicity

Age group

Rates per 100,000

Change,

2017-18

2017

2018

GENDER

93.0

–19.1%

Male

75.2

28.0

–7.5%

Female

25.9

RACE AND ETHNICITY

96.0

–21.6%

White

75.3

38.0

–14.5%

Black

32.5

64.0

–8.9%

Hispanic

58.3

AGE GROUP

22.0

–35.9%

15 to 24

14.1

77.0

–18.6%

25 to 34

62.7

126.0

–23.7%

35 to 44

96.2

119.0

–13.4%

45 to 54

103.0

36.0

+29.4%

55+

46.6

“I’m devastated that drug overdoses claimed the lives of 1,116 people last year,” Mayor Jim Kenney said. “Any life lost prematurely is tragic. But I am also hopeful that we are finally making progress in combating the worst public health crisis of our lifetime."

More takeaways from the health department’s report:

Overdose death rates dropped in all demographic groups, except for those over 55. Deaths in that age group increased by 29 percent between 2017 and 2018. Health officials saw another age-related shift as well: In 2017, people between 35 and 44 were the most likely age group to die of a drug overdose. In 2018, people between 45 and 54 were at “the most dangerous age” for drug overdoses, health department spokesperson James Garrow said.

Overdose death rates dropped across all racial and ethnic groups. Though the crisis has largely been painted as affecting mostly whites -- and white men still make up the largest group of deaths -- communities of color are also dealing with high overdose rates. Deaths among whites declined by 22 percent last year. Black overdose deaths dropped 14 percent. And overdose death rates among Hispanics -- which jumped 60 percent between 2016 and 2017 -- dropped by only 9 percent last year.

Fentanyl is still driving the most drug deaths in Philadelphia. It was involved in about 84 percent of deaths last year, the same as in 2017. The synthetic opioid has contaminated most of the city’s heroin supply, largely because it’s so much cheaper to produce than heroin and generates higher profits. Fentanyl is more powerful and addictive than heroin and sends people into withdrawal faster. Tolerance levels of many people in active addiction are now so high that heroin is not enough to stave off the painful symptoms of withdrawal, sending them to fentanyl.

Health department officials say they believe death rates are down because the city has increased treatment capacity and also distributed huge amounts of naloxone. The city has given out more than 78,000 doses since 2017, and trained more than 2,000 people to use it. Between January 2018 and April 2019, paramedics, police, and transit police administered 5,200 doses.

“Given all the effort and attention, it is disappointing [the 2018 decline is] not a significant improvement, but it’s going in the right direction," said Priya Mammen, an emergency physician and public health advocate based at the Lindy Institute of Urban Innovation at Drexel University.

Mammen said that to help people of all races with addiction, it’s essential for the medical establishment to diversify. “When you have a workforce that does not look like the population it’s serving — there’s no question that a more diverse workforce has an impact on survival.”

That’s because no single recovery solution will work for everyone, starting with the barriers that might keep different people from seeking help. “For some groups, stigma means shame. For other groups, stigma means jail,” she said.

Still, she praised the city’s progressive actions, including the naloxone distributions, and its conversations around a supervised injection site. “These discussions and thought processes are huge,” she said.

The latest report comes as the city wrestles over whether to create one or more places where people in addiction can use their drugs in the presence of medical staff who can revive them if needed, and refer them to treatment options.

Even with the slight decline, the 2018 death rate “is horrifying," said Ronda Goldfein, vice president of the Safehouse, the nonprofit formed to create and run the supervised injection sites. "That’s still three people a day. We’re gratified to see the number decrease, but it’s decreased from an unconscionable high to an unconscionable high.” Goldfein, head of the AIDS Law Project of Pennsylvania, is married to an Inquirer editor, David Lee Preston.

She noted that just like supervised injection sites, distributing naloxone is a way to keep people in addiction alive, and potentially able to seek recovery. If the drop in the death rate is due in part to naloxone, “that’s harm reduction," Goldfein said. "Harm reduction works, and a supervised injection site is harm reduction.”