In 1803, Philly physician identifies family of 'bleeders'

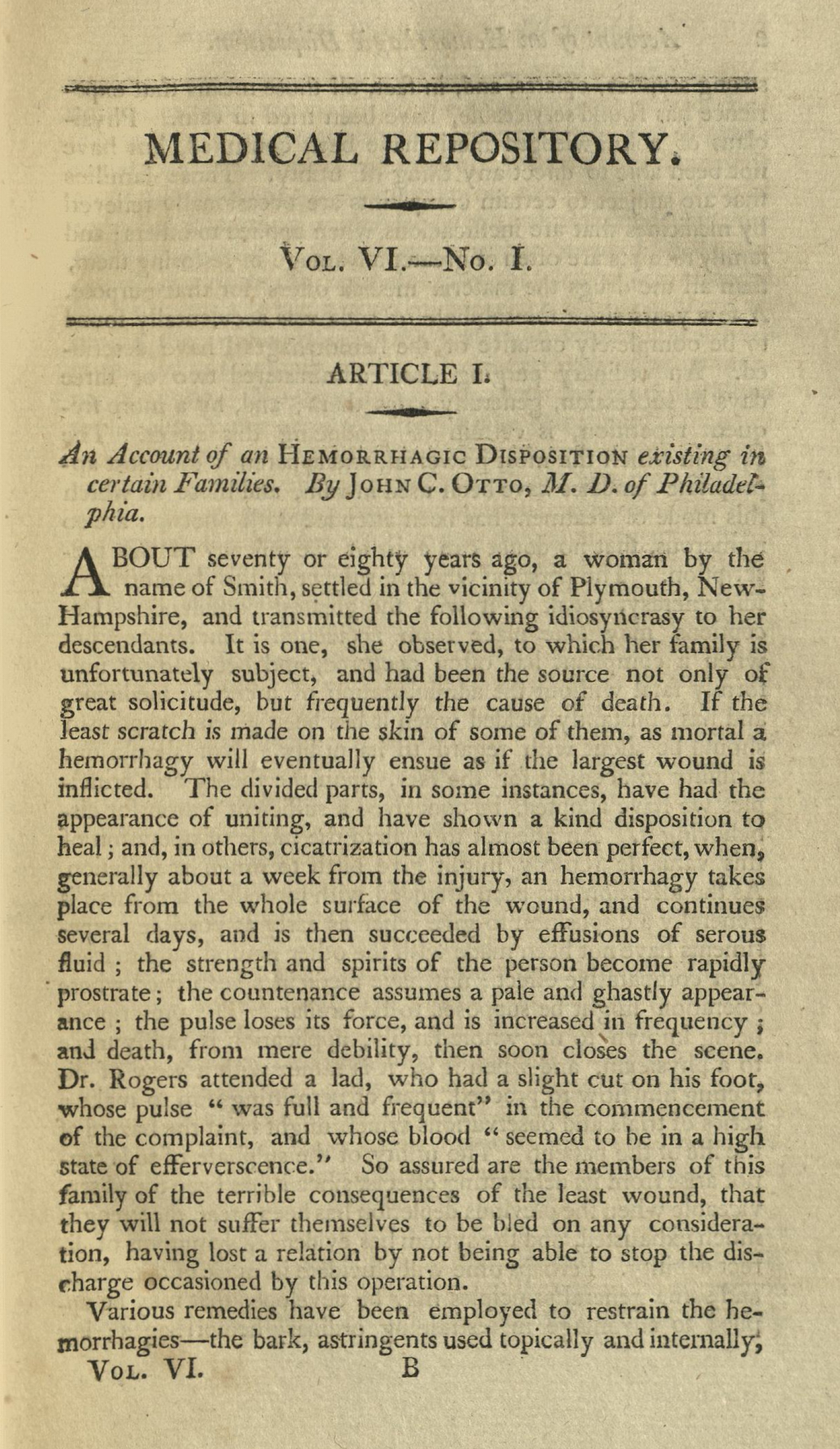

In 1803, Philadelphia physician John Conrad Otto published one of the first detailed accounts of a "hemorrhagic idiosyncrasy" that was passed down from generation to generation.

Today we call it hemophilia, and scientists have made dramatic strides in fighting the bleeding disorder.

But in the early 1800s, it was a mystery.

Writing in a journal called the Medical Repository, Otto traced the affliction to a New Hampshire woman who did not suffer from the disease yet had somehow transmitted it to her male descendants.

"If the least scratch is made on the skin of some of them, as mortal a hemorrhagy will eventually ensue as if the largest wound is inflicted," wrote Otto, who was born near Woodbury and did his medical training at the University of Pennsylvania.

A colleague told Otto that the blood of one such boy, who had suffered a slight cut on his foot, was "in a high state of effervescence."

Physicians had been noting similar cases for centuries.

[Philly doctor develops one-shot treatment for hemophilia]

In the 2nd century, Jewish scholars decreed a baby boy need not be circumcised if two of his brothers had previously died from the procedure, according to the National Hemophilia Foundation.

In the 10th century, Arab physician Abu al-Qasim described a blood disease that seemed to run in families, and identified three boys who had bled to death, according to the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine.

In the decades following Otto's contribution, the disorder became widely known as "the royal disease," as it ran in the ruling families of Russia, England, Germany, and Spain.

Queen Victoria of England was a carrier of the disease, and her son and three grandsons died of it. One of Victoria's granddaughters, Alexandra, married Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, and their son, Alexei, had hemophilia.

The boy's condition led his mother to rely on the counsel of the mystic Rasputin, who claimed to have healing powers. His influence on governmental affairs grew in the process, and some historians believe this may have fed the public distrust that led to the Russian revolution.

In 2009, geneticists identified the royal mutation as the one causing a form of the disease called hemophilia B.